As always in times of crisis, some will lose while others will profit. The COVID-19 outbreak has turned the tables, and major fund players are watching the market closely. For many of them, distressed debt is certainly an increasingly attractive area.

Record funds are being raised

There is no shortage of cash available, as both the number of funds looking to raise capital and the amount of capital targeted are increasing. For example, within one month of the US quarantine, Los Angeles based distressed asset manager Oaktree Capital Management sought over USD 15bn in distressed debt funding – the largest in its history. Goldman Sachs closed a USD 2.75bn fund of its own while New York’s Northwind Group launched a USD 220mn fund in May, and Brookfield is planning to start a USD 5bn retail fund. Other big names include Apollo Global Management, Carlyle Group and LCM Partners.

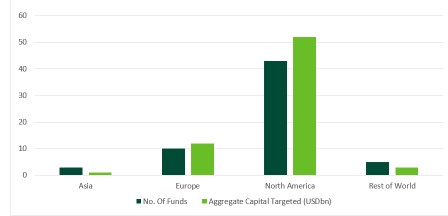

According to Prequin, the total raised capital could smash the record set in 2008. Out of 60 funds, 42 have a regional focus on North America and ten on Europe. But only seven of these funds are domiciled in Europe.

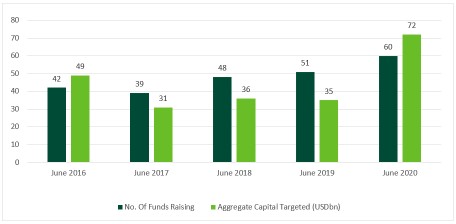

Figure 1: Distressed Debt Funds in Market, 2016-2020

*The number of funds is counted starting from the vintage year and not the launch date.

Source: Prequin

Figure 2: Distressed Debt Funds in Market by Region Focus, as of July 1, 2020

*The number of funds is counted starting from the vintage year and not the launch date.

Source: Prequin

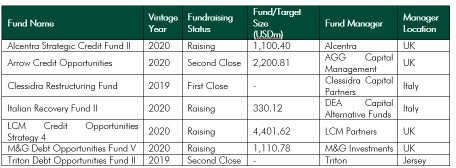

Figure 3: Distressed debt funds domiciled in Europe, as of July 1, 2020

Source: Prequin

Prequin data also shows that private debt firms have built up distressed debt funds over the past several years. As of June 2020, Prequin estimates that there is currently USD 68bn in capital awaiting deployment. These reserves are expected to be deployed in the coming months. For example, New York-based Centerbridge Partners activated a roughly USD 3bn capital pool that had been held on standby for four years.

The perfect storm

The build-up in credit markets that preceded the pandemic has been substantial. On the back of historically low interest rates and the persistent search for yield, both corporate and sovereign debt has grown since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). The decline in credit trends was visibly building up in the system even before the pandemic. This is often the case towards the end of what has been a very long expansion, where the underwriting standards tend to dip, and finance is secured for assets that should not be financed in the first place. Nevertheless, European banks have entered the COVID-19 pandemic with on average higher capital ratios compared with the 2008 crisis, and a credit boom did not precede the COVID-19 crisis. Nordic banks were, in general, well capitalized and entered the crisis in a strong position.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, various types of government liquidity measures have been applied across European countries, including deferral of tax and VAT payments. As these measures have supported liquidity, they have curbed part of the need for credit. The government stimulus packages have been strong, but they will be slowly receding. As central banks across Europe slowly curtail their monetary and fiscal measures, a spike in non-performing financial assets has been predicted (hotspots to include Germany, Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Spain and Turkey). This will result in debt markets adjusting to reflect the anticipated long-term effects of the pandemic on various industries; commercial real estate being one of them. Banks that are actively managing their balance sheets have been busy with selling troubled loans even before the outbreak of COVID-19. Particularly in sectors that depend on frequent human interactions such as transport, retail and hospitality, banks could go ahead with selling non-performing loans (NPLs).

Since the outbreak of the Coronavirus, Danish corporate borrowing from credit institutions has shown a weaker trend than in most countries in the euro area. One of the reasons behind this is the fact that – seen from an international perspective – GDP contraction in Denmark was at the smaller end of the scale. This was largely drawn by the fact that Danish production has not been shut down and because the composition of Danish production is less cyclically sensitive than, for example, in Germany and Sweden. Industries most severely impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak account for a relatively smaller share of value creation and total employment than, for example, in Spain and Italy. Another important factor impacting credit demand in Denmark was substantial consolidation of corporations right up to the outbreak, allowing them to cover part of their liability need by relying on their savings.

According to the Danish National Bank, the decline in total lending has taken place in the face of the central government’s guarantee of loans totaling DKK 9bn in connection with COVID-19. Corporations in agriculture, professional services and culture, entertainment and sports have reduced their bank lending, but growth in bank lending has declined across virtually all main industries.

Timing is key

In some European countries, such as Spain and Italy, the situation is expected to develop around further NPLs from banks to clear up legacy situations. For the Nordics, it is likely the opposite will apply with a strong banking sector built up since the GFC. Therefore, it will be more likely that specific one-off situations will gradually emerge in the more troubled sectors after the banks have eventually stopped supporting.

But the key questions now are a) when will these transactions come to the market and b) whether the opportunity set is really as large as anticipated.

The answer may depend on many factors, including the lenders’ willingness to accommodate troubled borrowers. High levels of NPLs have a threefold effect: they impair bank balance sheets, constrain credit growth and delay economic recovery. The data from the European Central Bank shows that dealing with NPLs is critical to economic recovery. Even if the economy rebounds quickly, cash flow and credit availability will be constrained. Some form of credit crunch behavior is a likely reaction of the banking system to an economic downturn. Voluntary or involuntary, banks become more cautious about lending. Furthermore, the extreme cost of fighting the pandemic has left many businesses with limited ability to incur further debt. The debtors will be constrained to exploring non-bank sources of financing, as traditional bank lenders might be looking to exit the credit either through foreclosure or sale to a distressed debt buyer.

Conclusion

Banks’ asset composition is expected to determine the extent to which they will be affected by the crisis. Although European banks have significantly improved their asset quality in recent years, the impact of the crisis on asset quality is a key concern.

Various market players suggest that distressed debt markets are at one of their highest peaks ever. During the 2008 financial crisis, a large part of the NPLs were businesses that were able to cover their operating costs but not debt costs. But while traditional recession usually results in a slowdown, the measures put in place following the COVID-19 outbreak have completely stopped activity in some sectors. The COVID-19 outbreak has, therefore, resulted in many healthy businesses being affected short-term, who otherwise would have had strong balance sheets and are now becoming increasingly attractive to investors.

The remainder of 2020 and 2021 will therefore be about businesses not being able to generate operating revenue. Funds might wait for the market to bottom out before deciding to actively buy debt at discounts. This could then further be used as a currency to acquire assets or businesses. Investors will be on the lookout for businesses with good long-term prospects that should be easier to get back on track.

Please contact Christian Bro Jansen or Dragana Marina if you have questions or would like to book a meeting.